‘Archaeology of Beasts’ by Monira Al Qadiri (Kuwait) opened at the Bozar Art Centre in Brussels in his Royal Rotunda, a creation by Victor Horta. Masonic overtones in the work of the creator of Art Nouveau in architecture serve as the perfect setting for the artist’s 4-part project on the theme of Ancient Egypt. The Masonic lodge in Brussels (which I visited once) is designed in a purely Egyptian style. Monira travelled to Luxor, the capital of Ancient Egypt, in Pandemic Covid 2020 and immersed herself in its rich history. The young woman lives in Berlin, in close proximity to the Neues Museum, which, in addition to the bust of Nefertiti, houses statues, sarcophagi, papyri and other artefacts spanning from the Ancient Kingdom to the later eras of the Egyptian state. Immersion in anthropomorphic culture gave birth to her project, in which Egyptian myths respond to the challenges of modern society. With an appropriate use of AI and virtual reality. Monira herself, like the ancient Egyptian goddess of love Hathor, is culturally diverse. Born in Senegal, raised in Japan, positioning herself as a Kuwaiti artist living in Berlin, she is a product of multiculturalism. An eloquent Japanese minimalism is evident in her artistic practices.

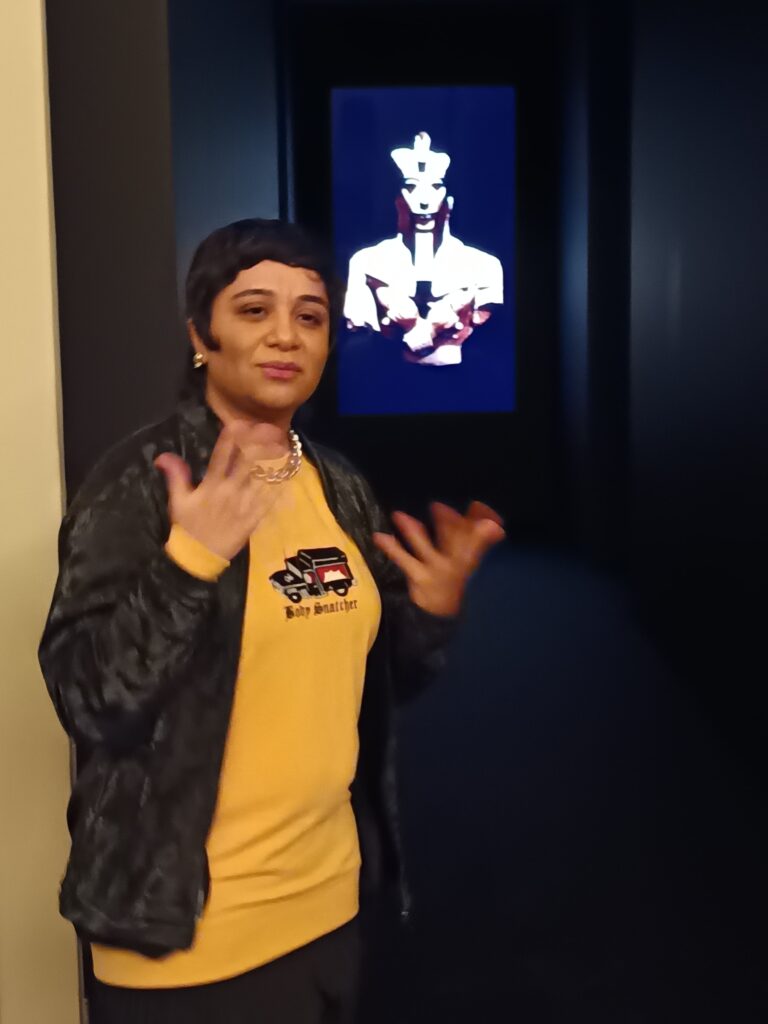

In a narrow, tomb-like corridor, seven 3D scanned statues from museum exhibitions come to life, animated and talking to each other in voices generated by artificial intelligence. At the centre stands Ehnaton, the only human figure, surrounded by statues of ancient Egyptian animal deities. Passages from the Egyptian Book of the Dead, a collection of myths, prayers and incantations that guide the deceased through the afterlife, are here reimagined as a dialogue between humanity and those it considers beneath it. The texts are frighteningly relevant, the atmosphere of being in the dark between deities is mesmerising.

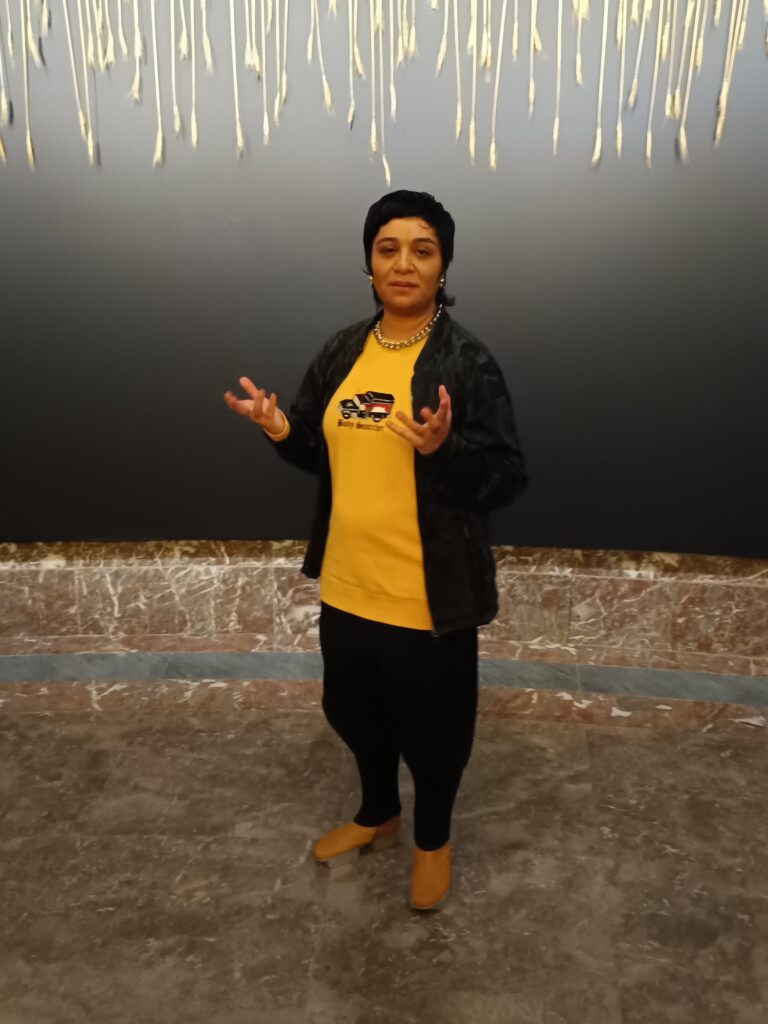

Unlike monotheistic religions, where Heaven is a place of well-deserved idleness, the Ancient Egyptians believed that Heaven consisted of fields of golden wheat where the dead could continue to farm after they had passed into the next world. As preparation for these heavenly duties, the dead were often buried with their scythes and farming implements. On the black-on-black wall of Monira’s installation is a long row of gilded wheat, each stalk symbolising the souls of the deceased. The ancient view of eternity honours labour, the cultivation of the land and the enduring cycles of life. Using virtual reality, the artist depicts a field of wheat where the myth of the Heavenly Cow appears, VR in the viewer’s mind correlates with the otherworld in a 360-degree view.

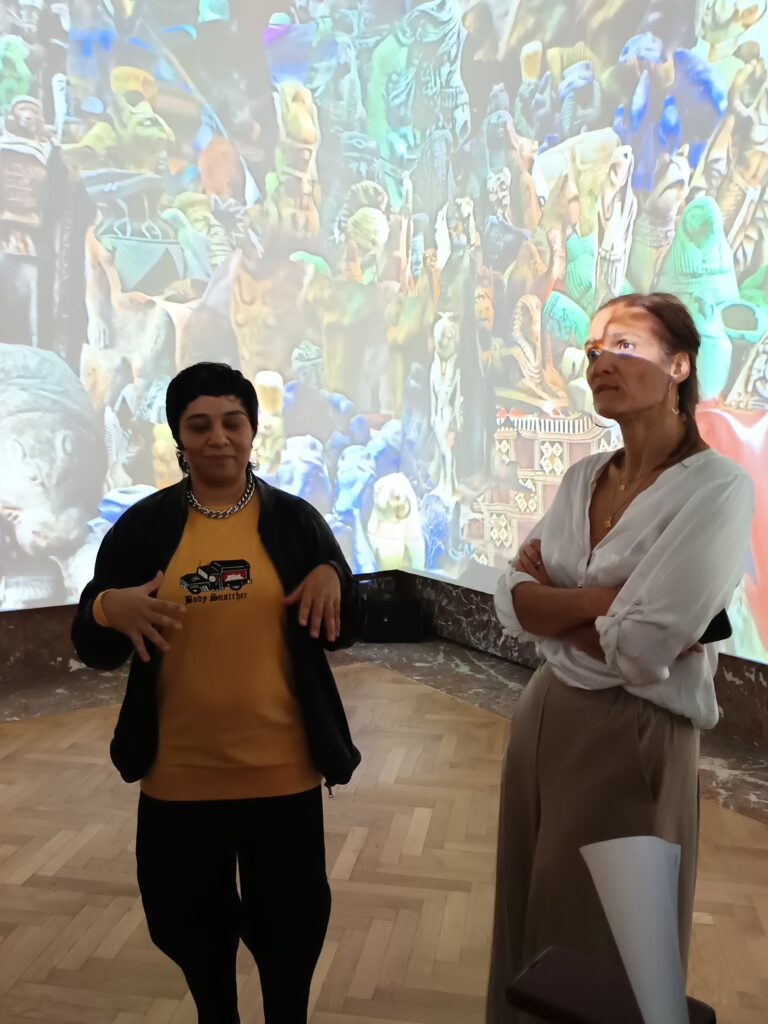

To bring the viewer closer to Egypt, the artist reminds them of the hundreds of souvenirs that sometimes haunt us obsessively in modern Egypt. Scanned in 3D from the street markets of Luxor, they form digital ‘mounds’ of creatures piled on top of each other, surrounding the viewer, creating a warped and distorted landscape with different anatomies. Tiny bodies; large bodies: strange bodies; stretched bodies: incomplete bodies merge to form this chaotic texture, each contributing to this disturbing picture that evokes an allegory of otherness.

Two hypermasculine statues of anthropomorphic ancient Egyptian animal deities rotate quietly, reminiscent of exhibits at a luxury car show. Originally intended for home décor, they have been repainted in glossy black, emphasising the exaggerated musculature of their humanoid bodies. The two gods Anubis and Khnum face each other as if locked in confrontation, their shadowy figures frozen in tense opposition. The opposition that occurs between man and animal also extends to man and other humans: who is considered fully human, and who is relegated to the status of ‘beast’? Those who are categorised as ‘beasts’ are too often seen as automatons without will or political influence, relegated to the realms of eroticism or death.

In Luxor’s Valley of the Dead, Monira literally fell in love with the image of Queen Hatshepsut, and it may be that her next project will focus on her erotic images.